There have been many words used to describe the world inhabited by the characters in a Roman Polanski film. Disturbing, disconcerting, alarming and distressing are among the descriptors that are among the most common. To me, the word unsettling is an appropriate adjective for the often bizarre circumstances that identify these scenarios. Of all his works, Death and the Maiden (1994) is about as unsettling and troubling a world as Polanski has presented on screen.

The story, set in an unnamed South American country of recent times, involves only three characters: Paulina Escobar, her husband Gerardo, a distinguished attorney and Roberto Miranda, a prominent doctor. Paulina is at her seaside home, dining by herself, as she waits for her husband to make his way through a particularly violent storm late at night. He has had a flat tire and has been rescued by Dr. Miranda, who drives him to the security of his home.

As Paulina and Gerardo talk, we learn that he will be heading a commission that will investigate ghastly crimes and human rights violations perpetrated by the previous regime. Paulina has a special interest in this, as she was one of the victims, brutally tortured and raped; she befell this fate, as she was a political activist who spoke out against the government. The commission however will only be looking into cases of victims who were killed. She argues with her husband to use his influence to change this so that every case is examined.

Dr. Miranda has left the Escobar house to make his way home, but soon returns with the flat tire belonging to Gerardo. Grateful, Escobar invites the doctor into his home on this gloomy evening for a drink. It is then that Paulina, upon hearing his voice and peculiar laugh, realizes that this is the man who raped her on several occasions.

Revenge is now the primary concern for her and soon after her husband falls asleep, she hatches her plans to exact that payback. She bounds and gags Miranda - even going so far as stuffing the panties she is wearing in his mouth and then taping it shut - and ties him securely to a chair. She pistol whips him, drawing blood and then proceeds to remind the doctor of what he did to her. To make the memory more vivid, she plays a tape of Schubert's "Death and the Maiden" concerto; this is the same music that the doctor played for her during his beastly behavior. (The title of this music is, of course, disarmingly ironic, as is the sweeping beauty of Schubert's melodies being played to accompany such brutality.)

Gerardo awakens to this madness and tells his wife that he must untie the doctor, who is professing his innocence. She refuses and then tells Gerardo in private many of the details of her suffering. This is a critical detail, as she had not previously informed her husband of all the specifics. Though a bit unsure at first, Gerardo slowly begins to believe his wife and takes her side in her actions to force an admission of guilt from him.

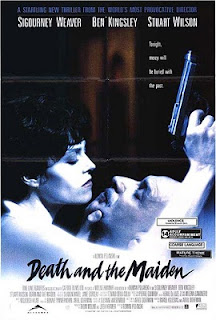

During this film, based on a play by Ariel Dorfman, Polanski rarely lets up on the intensity of this macabre chain of events. Paulina (brilliantly portrayed by Sigourney Weaver) is liked a trapped animal who has been briefly let out of her cage and is ready to pounce. Her actions of course are somewhat comparable to that Miranda, though not as deviant. Yet, she crosses the line, acting as judge and jury and does not care how much she abuses or embarrasses him (going so far as holding his penis while he urinates, as his hands are tied).

This is arguably Weaver's finest film performance, as she finds tremendous emotional range, while always maintaining total control. It is especially impressive to listen to the tone of her voice as she recalls the brutalities of the past. She has portrayed a number of strong women throughout her career, but none as dominating or as disturbed as this and it is her performance that is the centerpiece of this work.

Another brilliant performance comes from Ben Kingsley as Dr. Miranda. You can almost feel his heart beat accelerate through this ordeal, as he steadfastly denies his role in prior crimes. The glazed look in his eyes combined with the slightly off-key delivery of his lines is a memorable presentation of a man who is angry, confused and worried for his life.

Both characters have taken the law into their own hands: Miranda in the past and Paulina in the present. Power and "right" define their actions; Paulina, believing that the commission that will be headed by her husband will do little, thinks that she must decide the fate of Miranda. The doctor, a respected member of the local community (he wears a casual but elegant sports coat), acted as he did for numerous reasons, including the morbid fact that he liked raping Paulina.

I couldn't help but think of the character of Noah Cross in Chinatown (1974), who raped his daughter and then figuratively raped the farmers in the valley, by circumventing their water supply, so as to depreciate the value of their land. He lives on, going about his business in his own charming (in his view) way. Similarly, Dr. Miranda has been living the life of a first-rate individual, his crimes unpunished until this fateful evening.

At the film's end, there is a sense of victory (if you can call it that) for Paulina, but under questionable circumstances. The doctor has been proven guilty, but he is allowed to live. How many other women are out there who were similarly brutalized that will never know their attackers?

In this way, the evil lives on, as it does in Chinatown and several other Polanski films. The world is an unsettling place where uncovering the truth can often lead to the realization that no one is innocent.